In the days leading up to the U.S. Civil War, fugitive slaves headed north from the slave-holding states of the U.S. South on their way to liberty in Canada. As many as 100,000 freedom-seekers used the Underground Railroad, a network of people that assisted escaped slaves along their journey and gave them a place to stay until it was safe to continue to the next “station.”

Many passed through New York, notably Montgomery County and the surrounding region of Central New York State. The area’s many waterways, including the Mohawk River and the Erie Canal, provided stealthy transport for the northbound travelers under the cover of night. Furthermore, the religious faith of the area’s residents led to the growth of a strong abolitionist movement and word got out that this was a welcoming community to stop in during the long trek to the Canadian border.

Visitors to this region can trace the journeys of those who traveled along the Underground Railroad and learn about the work of the citizens who helped them on their way to liberation.

Though initially the lands north of Pennsylvania were considered relatively safe for escaped slaves because of widespread support for the abolitionist movement, the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in September 1850 forced those who worked along the Underground Railroad to persevere in secret.

The act required that all escaped slaves, whether apprehended in southern slave-holding states or in the free north, be returned to their owners. Though it was eventually repealed in 1864, its enactment only strengthened the resolve of abolitionists in the northern states. The penalty for helping runaway slaves was steep – up to a $1,000 fine or six months’ imprisonment – but the people believed strongly enough in freedom for all humans that they took the chance to live up to their beliefs.

Amsterdam

Amsterdam, which straddles the Mohawk River, was home to numerous stationmasters for the Underground Railroad. Ellis Clizbe was an abolitionist and a founding member of the anti-slavery societies of both Amsterdam and Montgomery County. Known to shelter escaped slaves on his farm in the Rockton section of the city, Clizbe’s determined work lead to Amsterdam’s reputation as an “abolition hole” and a stronghold of the movement in New York State.

Another prominent city businessman, Chandler Bartlett, provided shelter for those seeking freedom in his shoe store on Main Street.

Take a self-guided walking tour of the town’s 41-acre Green Hill Cemetery. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, it contains the graves of many residents of Amsterdam, both white and black, who fought against slavery.

Canajoharie

Twenty-two miles west along the Mohawk River sits the town of Canajoharie, another important locale for abolitionism in Montgomery County. The county historian created a self-guided walking tour of the abolitionist movement in the town that points out places of note still standing, as well as the locations of homes and businesses that are lost to time.

One historic home is that of Chester “Bromley” and Elizabeth Phillips Hoke. Descendants of grandparents who had been locally enslaved, it stands to represent the role that African Americans played in developing the economic and social development of the Mohawk Valley. Chester served in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, one of the nation’s first blacks troops to fight in the Civil War.

The Canajoharie Academy, once located on Otsego Street, is best known for its former headmistress, a powerhouse in the history of reform movements in the United States, Susan B. Anthony. Another notable piece of history in the town is the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. A group of five African American men had purchased a plot of land on Cliff Street and incorporated the church in 1857, though it is not known whether a physical building was ever constructed. A former slave, the Reverend Richard Eastup, oversaw the church, whose denomination was commonly affiliated with such leaders of the movement as Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass.

Western Montgomery County

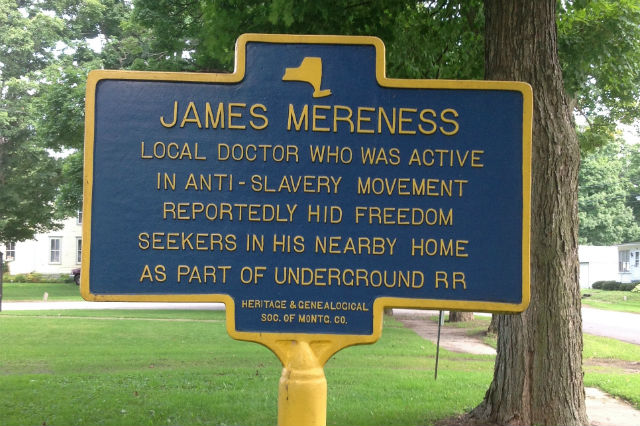

In the village of Ames, Dr. James Mereness participated and organized anti-slavery meetings for the western part of Montgomery County for many years prior to the Civil War. Reports indicate that fugitive slaves seeking freedom from their lives in servitude sought shelter in Mereness’ home as part of the Underground Railroad network. Dr. Mereness died in 1872 but continued his interests in improving the lives of African Americans through bequests to educate them.

In the village of St. Johnsville where the picturesque Timmerman Creek runs into the Mohawk River, Daniel Leonard and his partner built a grist mill just north of the Mohawk Turnpike. Local lore has it that freedom seekers escaping slavery, hid in rooms below the mill. When water to the thirty-foot water wheel was shut off at night, the freedom seekers could make their way via a tunnel to the creek and continue their journey north and westward to freedom.

Today the mill operates as the Inn by the Mill bed-and-breakfast, where the owners happily show off the rooms where the freedom seekers waited to continue their journey to freedom.

Oneida County

The abolitionist movement was also strong to the west of Montgomery County in Oneida County, with 17 anti-slavery societies existing in the mid- to late 19th century. Today, visitors can see one of the few remaining landmarks of this time, the former Mechanics Hall, on the corner of Hotel and Liberty Streets. In this building, abolitionists held anti-slavery events and rallies, including one in 1857 that was attended by William Lloyd Garrison and Susan B. Anthony.

More Information

Maps of both the self-guided walk in Canajoharie and the Green Hill Cemetery, as well as descriptions of the famous plots found there. A full Underground Railroad itinerary is available through the Montgomery website.

Lodging in Montgomery County ranges from country inns to B&Bs to several hotel and motel chains.